Russian Diary

1991

Yevgeniya Moiseyevna says that there was only a three-year period in her life, from 1924 to 1927, when the shelves in the shops were always full, but then everything was so expensive, that you – again – couldn’t buy anything as a result. She has spent the rest of her life hunting for bread and other basic things, or standing in line. She is now 83 years old and preparing to go abroad for the first time.

There is no bus service at the Sukhumi Airport; the sixty passengers had to carry their luggage themselves to the plane, accompanied by the airport dogs. There is no baggage carousel either, on arrival the suitcases were brought in on wheelbarrows.

*

Yesterday our Russian hosts asked us how we had been able to spend that much time among Georgians. Then one of them suggested in a condescending tone that we drink to the freedom of Hungary, adding that he did not understand what our problem had been with them. The English guy was very sympathetic towards the Russians who are only now beginning to lose their colonies, like England did way before them. Later it turned out that two Scots were also staying at our hotel, so the guy explained how much he hated the Scots, the Welsh and the Irish.

*

On the beach in Sukhumi, three Russians were sitting near us; they were chatting about what a pity it was to let Eastern Europe out of their hands. Igor was barely willing to lie with us on the public beach, preferring to go to the ministerial beach where he could finally see ordinary Russian faces – as mostly Russians go there for holidays. But that’s still nothing. We were visiting with Georgians, and at the huge dinner table, where he was also invited, he began to scold the Georgians – and, by the way, the Hungarians too – for all being leeches on Russia’s body. The Georgian physicist was very offended, but then it turned out that she also had a discriminatory soul. She said that school in Georgia only starts in October so that the children can rest while the weather is warm. But in early September I saw schoolchildren in town, and when I mentioned that she said, oh, they’re just Abkhazians, as if they weren’t even kids. She also passed remarks on the Abkhazians; that they had no culture and that it had always been Georgia here. But the Abkhazians gave as good as they got claiming the same thing about the Georgians: that they had no culture, they only took it from them, and this place had always been Abkhazia.

*

One evening in the Vremya [television news] they showed that the shelves in Hungarian shops were crammed with huge pieces of meat – the continuation of the news was that we cannot sell them abroad; Igor said that this is why his mother has to queue at 6 in the morning because we have everything – because they are so kind-hearted that they give us everything and there’s nothing left for them. In a word, he reckons that they are starving in the largest country in the world and there is nothing in the shops because they are giving everything to one of the smallest countries in the world to keep its people well-fed. He thinks it is much better to bathe in the Volga than in the Black Sea, and he also wanted me to say that Crimea is more beautiful than the Caucasus (although Crimea is no longer in Russia but in Ukraine). It is as if the beauty of a landscape is determined by His being Russian. (By the way, he is half-Ukrainian.) Our Georgian landlady said she wouldn’t have let any Russians in her house if he hadn’t come with us.

*

The Serbian guest also arrived at the conference; he brought up how horrible the Croats are, no matter that they want to exterminate each other, so obviously the Serbs are just as terrible.

*

Olya from Leningrad was traveling on a trolleybus in Sukhumi in ’89 when Georgians boarded it and wanted to shoot the driver because he looked like an Abkhazian. A gun was pressed to his head and the only thing that saved his life was that he had his ID, which stated that he was Armenian.

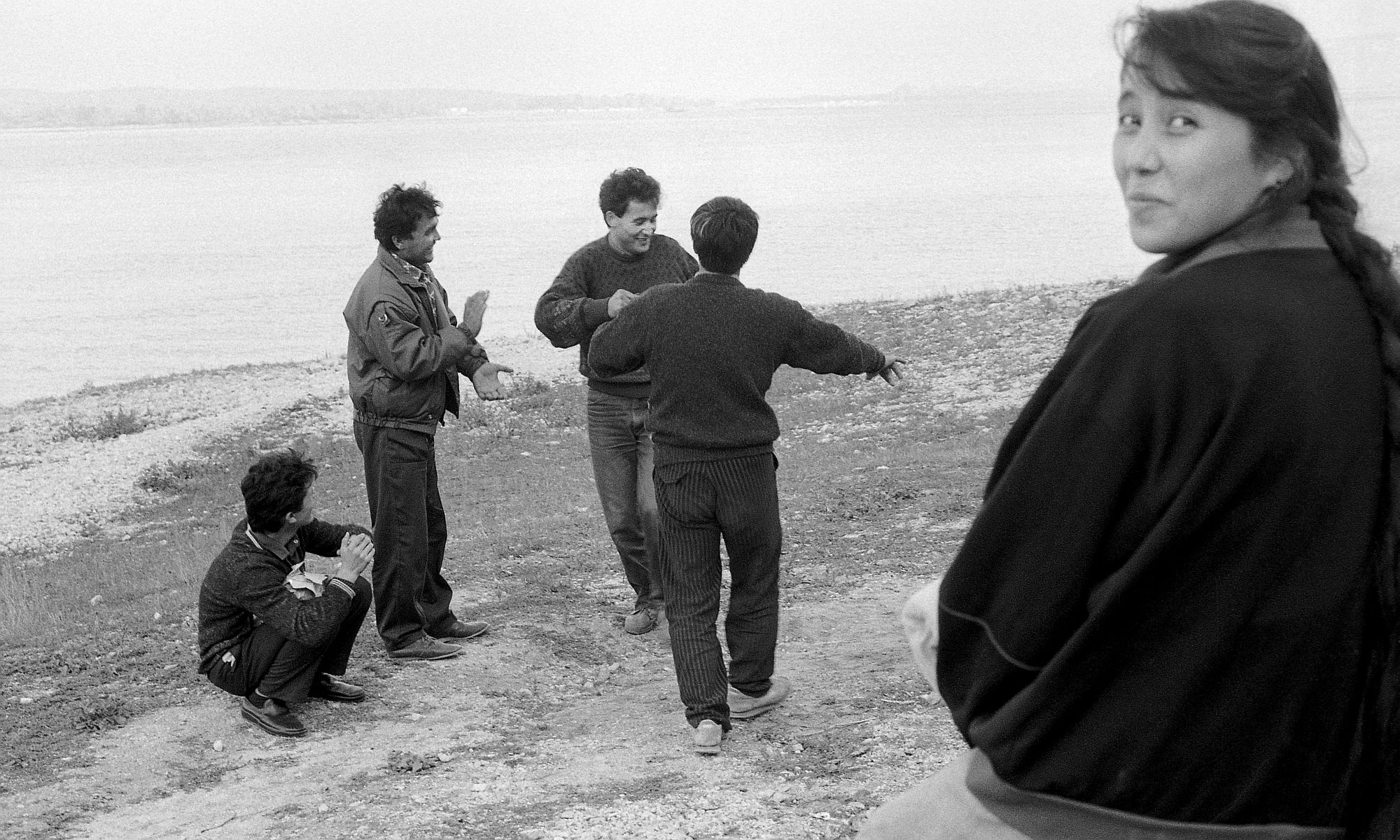

On the boat trip on the Volga to the village of Shiryaevo we were accompanied by literary students from the university, all Tajiks. They entertained us at their own expense: they invited everyone, all of them chipped in, cooked in the yard of a village house, and made a huge table for the conference participants. The Russian organizer did not fail to mention that “these slant-eyed” were studying here on Russian money.

*

The poetess (Russian), who lives in Georgia said on the local TV channel that it would be better for Georgians and Abkhazians to get on well and live in peace with each other, as they used to; Georgians reacted by threatening to shoot her if she went on talking like that.

*

Now the Irish were at each other’s throats again, so the English remarked that the Irish should not be taken seriously, they are not even a people.

*

We were asked on the ship where we had got our tan; the well-decorated old veteran woman was also amazed that we had been able to be among Georgians for so long.

*

On the ship we were watching the news on the TV, and it was announced that a monastery previously used by the KGB had been returned to the church. An old man said to another that it was terrible, we fought against religion for 70 years and now they are back! This is a new generation – said the other – they think differently now. The first retorted: But our sons are the new generation; this means we have raised our sons the wrong way!

*

September 23.

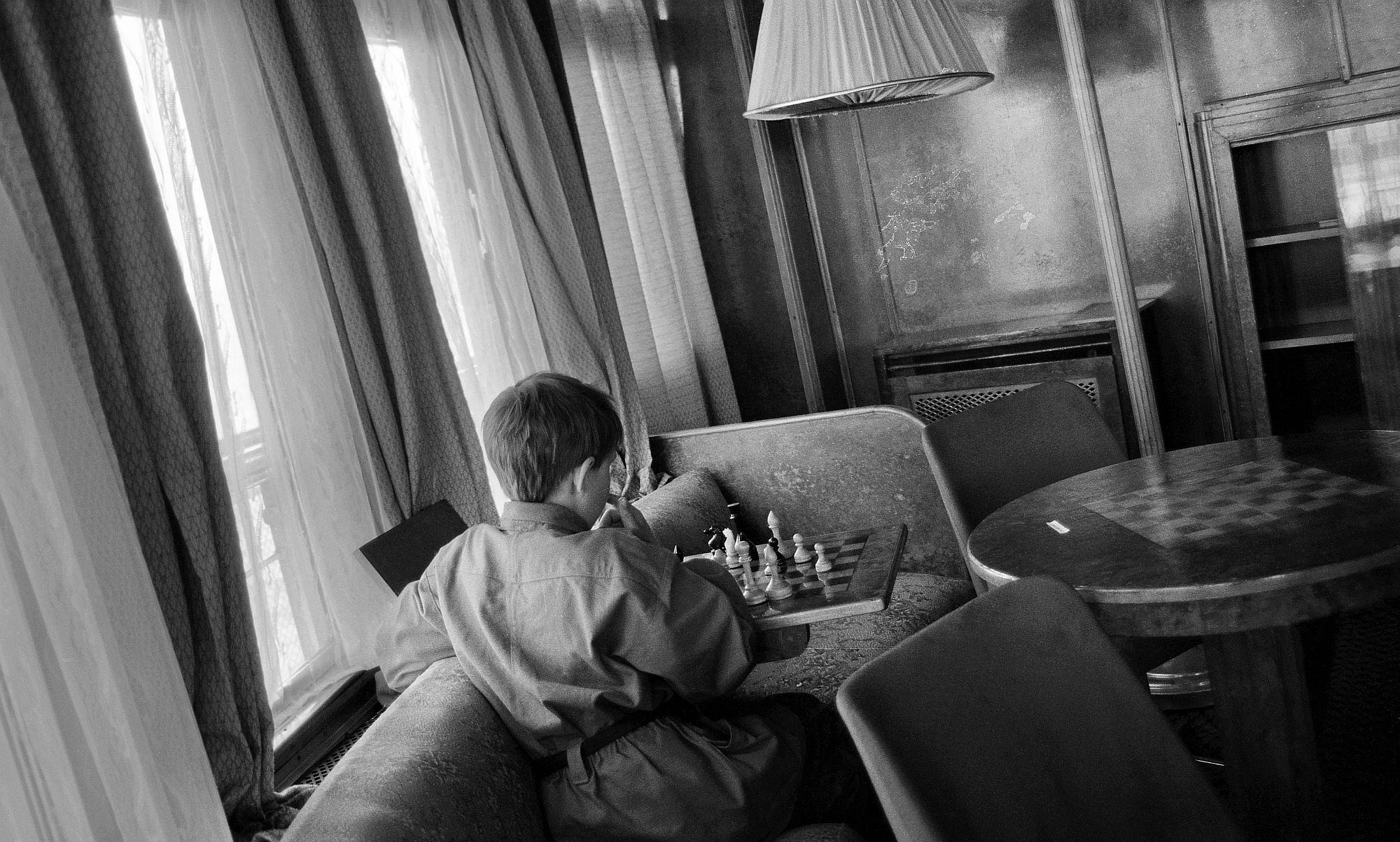

We left Samara at six o’clock in the evening on a ship called Sergey Lazo. It’s much more beautiful, though much less comfortable than Peter I we took when cruising on the sea. It is all made of wood and the furniture is beautiful. There is a pleasant living room, more specifically a reading room with tables, so you don’t have to be crammed into the tight cabins. The TV only works in the harbor, so it is peaceful here. Although none of the table lamps have bulbs, one can still see relatively well.

September 24.

First-class orienteering course. In the morning, an undulating line of low mountains to the right, some cities with wooden houses, and everywhere forests turning yellow. The water is very wide, you can’t even tell how much so because I think I see a shore and then it turns out to be just an island. Old women wrapped in thick shawls and coats sit in the windows or on the deck. They travel down the Volga every year, it is an old custom here; Chekhov made this trip several times. It’s not even like a river, but a lake with many islands. We got off in the town of Saratov for an hour, went to the main pedestrian street; there was a Szombathely feel to it.

September 25.

Every morning is a surprise. Now the coast is not visible at all, it is as if we were traveling by sea, only the waves are smaller. It’s foggy gray weather, there was a little rain, but the air is no longer so biting cold. Around half past three at night it was refreshing to stay a bit on the deck and watch the full moon. Passengers stroll around on the deck in their coats.

We moored in Volzhsky for half an hour. Now the sun is shining, we are coming out from the cold into the warm again. You can sunbathe without a jacket, no need to sit behind the window. We couldn’t buy matches here either; you can only get them with coupons.

We stopped in Volgograd for three hours, there was a bookstore where I finally got something to read, and in addition I could buy the book by Alíz [Mosonyi],I’m Nine Years Old and another similar one. I bought another Czech album, a pretty massive piece, over 400 pages full of beautiful pictures from between 1839 and 1914. No small task to carry it home, but it’s okay.

There is a state of emergency in Tbilisi.

September 26.

We arrived in Astrakhan in the afternoon.

September 27.

Paris, Copenhagen, Astrakhan – each one a birthday. In the morning we ate melons, I photographed old Kalmucks in the city; one said that he fought in the war in Hungary, and added that the Lake Balaton and the Danube are beautiful, and there is Buda and Pest and his decorations were all there on his jacket. It is an almost Southern atmosphere, although the palm trees are missing. When we sailed off, the military music was turned on, the harbor dogs and cats gathered around the ship, some people were waving, and by the time we left town the sun had set. I regret that we couldn’t see the Caspian Sea, but there was no vehicle available to take you there and bring you back. As early as half past five in the morning, passengers grabbed their bags and went shopping. This early, the watermelon costs only sixty kopecks, later it will be seventy. In the evening we drank cognac from Dagestan on the boat, there was nothing else we could buy.

September 28.

In the morning we stopped in the village of Nikolskoye for a short time. This is a real dump; Igor says, of course, Astrakhan is a dump, too, compared to Samara. The locals were waiting for us in the harbor with an impromptu market – the most important commodity here is fish and melon, the buying and selling takes place with large clouds of dust in the background; by the time the ship reaches the open water the vendors have already disappeared.

Here, too, the houses are made of wood. Aktyubinsk is the next stop; everyone rushed to buy melons here too; maybe they have already eaten everything they bought in the previous market? We barely left the city we saw a wedding crowd on the edge of the coastal forest, with the bride and the groom, the ship is blasting its horn at them, they are honking back on their car horns; waving back and forth. By the time we got to Kamenny Yar it was dark, but the market was kept all the same. They switched on a big searchlight on the ship and pointed it at the vendors.

Big red prawns were sold here, everyone bought bags of them, and I ate a fried Volga fish. After the lights turned on I could see through the windows into the cabins – there are large melons lying in nice rows on the beds.

September 29.

We left Volgograd at eight in the morning. Passengers were asked over the radio to go out on the deck and take a farewell look at the heroic city. Afterwards an event was held to commemorate the Battle of Stalingrad. We were also instructed over the radio not to throw bread to the seagulls because bread is the property of the people.

We went through a lock again, there were two chambers, we rose like ten meters in both of them, taking eight minutes each time.

Volzhsky – hats, shawls, socks made of some kind of angora are sold here. Now the clouds have gathered again, sometimes the sun is still shining, but it’s already cooler. Yesterday it was even possible to sunbathe in a swimsuit, today the old ladies are again circling in their coats. There are also sailboats on the water.

There were only three old market women in Dubovka with a couple of bags with plums, we were just stopping here for five minutes, people barely streamed out, they immediately returned. In Primorsk, melon was the main hit again, I bought one too. It was still possible to sit in the sun for a while, now there are barren hills on the shore, the other shore is far, far away. The old man joined the card party. It’s awful that I don’t have binoculars, I still regret not buying them in Vilnius at the time. I would be able to watch the shore much better.

Balikley – some kind of sheep’s wool is sold here. Local old women came aboard the boat in the hope that the boat from the big city had everything, and they stood in front of the buffet for a while, which had nothing in it and wasn’t even open. It only has some kind of very expensive cognac and western cigarettes. When we leave one of the bigger cities, the buffet carries some kefir or mineral water, but we have to hurry because everything runs out in minutes. In Antipovka the same scene: passengers out, locals in. This may be a larger place because the wharf is a fine wooden structure, and the market is set up on asphalt and not in the dust. We bought raspberries. It’s getting dark after five. I saw a bright shooting star. I went to a cinema in the evening. The projector was awful. Sometimes the center of the image was almost sharp, but mostly not, the degree of blurriness fluctuates, the image quality was better here and there.

September 30.

We were in Saratov all morning, walking through the city center again, now more leisurely than last time. Here, too, there is a CUM store, only smaller than in Moscow. A ship called Komarno stood next to ours and the big hotel is called Slovakia. The sun is still shining today, but there is a rather cold wind.

The fall colors were beautiful in the afternoon, the sky and water shining blue, yellowing forests on the shore. There is nothing nicer than traveling by boat. When I stand on the stern, there is no engine noise, the boat just glides in silence and the wind brings the scent of autumn forests.

The guy next door is seventy years old, he could have retired a long time ago, but he works in a chicken hatchery because that way he gets thirty eggs and three chickens a month for free, which is a very big treasure. That’s why he gets up every morning at five, spends forty minutes on the bus to the station, from there another half an hour by electrichka [local train] and a quarter of an hour on foot. If someone’s wife also work there, that means six chickens a month and sixty eggs. He also said how good it was to be able to get matches in Astrakhan without a coupon. We answered we hadn’t seen one single match there, and he replied that he hadn’t either but he knew that there they weren’t rationed, and how good that was.

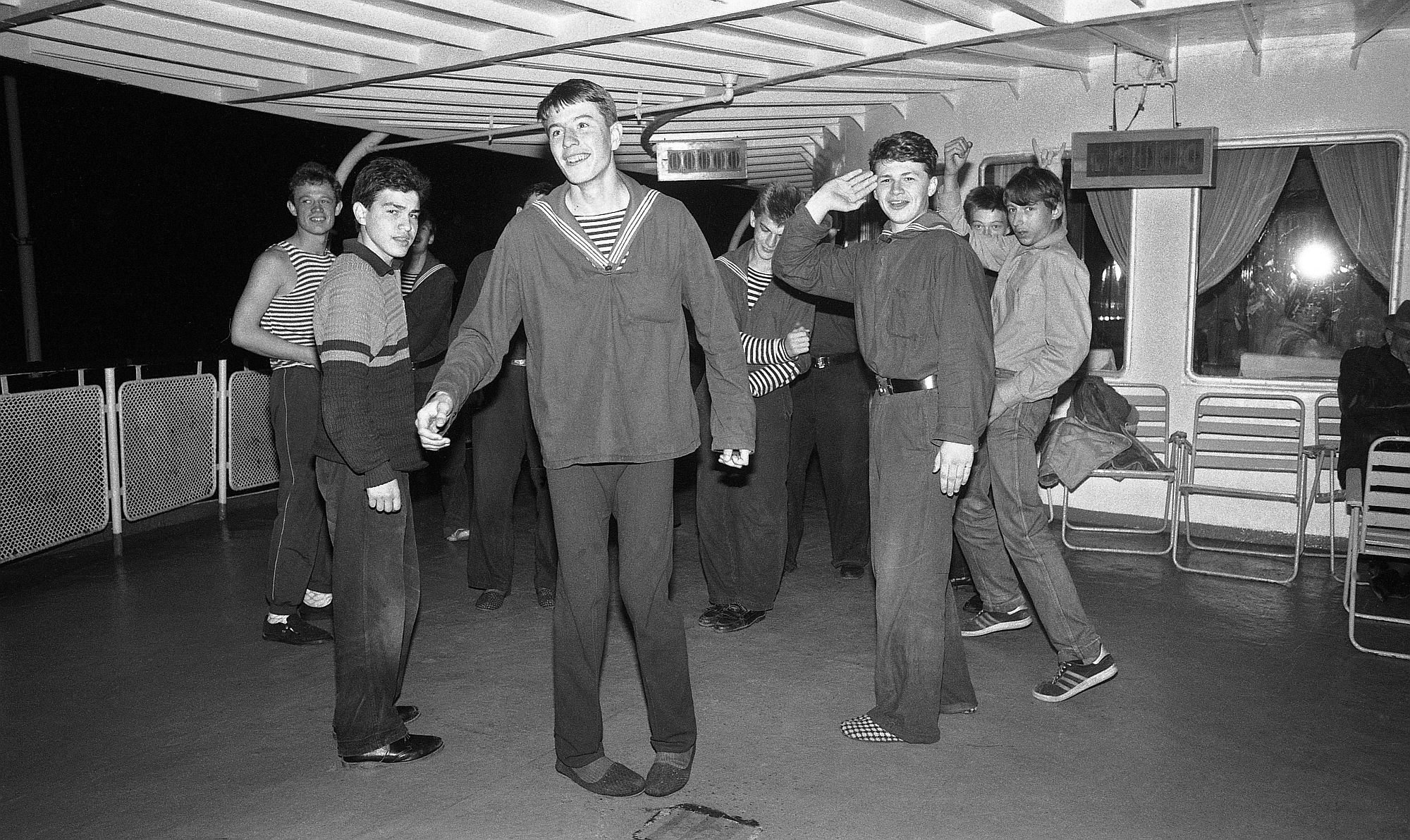

In the evening we went through another lock, a whole little house party was thrown on board while we were in the chamber. There was disco music on our ship and the sailor cadets were dancing, and girls were dancing on the other ship. The lock allows two vessels to pass through at the same time. They shout out: where did you come from? – From Cheboksary, and you? – From Nizhny Novgorod! – then waving good bye.

October 1.

There was a thick fog this morning, so we were stuck for two and a half hours out on the water, half an hour away from the port of Syzran. But then the sun came out a bit and we were only one hour late for Samara. Here we lay next to a ship called L. Dovlatov, this was the one with us in the lock yesterday.

It is thirty degrees in Sukhumi and twenty-eight in Pest. And here it’s very cold.

It was mentioned that Kazan is a very nice city, but we won’t be able to see it, unfortunately, because we’ll be there at night. Igor, of course, remarked that it can’t be so beautiful because it’s not Russian.

In Samara, the conference organizer was waiting for us at the port with more business offers and again he wanted to take us to a painter to buy pictures.

October 2.

We were in Ulyanovsk this morning; quite a noisy, smelly, unpleasant place. From the port, we took a bus into the city, there were only children besides us, and the tour guide delivered a speech that lasted the whole ride that would have won him praise even in the fifties. Lenin was born here, this is Lenin Street, this the Lenin Museum, this and that much textile is produced in Ulyanovsk, how the economy developed, this is the Lenin’s Sisters High School, Lenin’s birthplace, and so on. This must be extremely interesting for the kids.

The old waitress told everyone how rich we were that we ordered all the dishes, even though others here were asking for half-portions, and were bargaining. A whole portion is pretty small of course, I don’t know whom the half of it would be enough for?

In Volgograd we drank a can of beer on the bench, kids rushed towards us asking for the can, I could barely swallow the beer in my confusion, they stood around us in such a tight ring. For an average Russian it’s so expensive that they obviously don’t buy it, so it’s hard to come by cans.

Among the Bulgakov scholars there is an old Russian woman, she lives in America but was born in Samara, and she was told by her parents during the Samara famine of 1922–24 not to buy pirogs on the street because they are filled with human flesh. So she didn’t want to come to Samara because she is always reminded of this whenever there is talk about Samara; it’s true that she’s rather old, too.

I heard two similar stories about the siege of Leningrad. An old woman in her childhood was called over by a neighbor to eat roast meat, she didn’t understand where it was from, so she was told not to be scared, it was fresh, one of the residents from the building next door had died only just now. Another little girl was given broth, and only when she had eaten it was she told that it was made from human flesh. Some cut off the bone buttons from the bed linen and boiled them up for soup.

We have not stopped since Simbirsk-Ulyanovsk, and unfortunately it has got dark, although the Kama joins the Volga somewhere along this reach, but we couldn’t see it. The Milky Way, on the other hand, and all the constellations are in full view. Shooting stars also appear, if I remember correctly there is also a meteor shower in early October, which makes shooting stars common. It’s only that the weather is a little too chilly and windy to stand outside for too long. I didn’t see much of Kazan, we arrived at ten in the evening, visitors to the capital of Tatarstan are greeted by a huge welcome sign, one or two Tartars were dozing at the station, but there was nothing worth mentioning in the port, only two dogs hanging around.

October 3.

We reached Cheboksary in the morning, on the land of the Chuvash. Igor said it was also a dump, he refused to walk with us, said that he had seen enough wooden houses, they were nothing new to him and he went to buy newspapers instead. But I liked the place very much. It’s true that I only saw the old quarter along the Volga, where there were wooden houses and a church that was built in the seventeenth century, and for me this one was the most beautiful so far. It was full of frescoes, but they did not look like as if they were painted, but as if the pictures had been burned into the wall, they were black, as if the building had burned down, but on closer inspection they were just painted like that. It’s also one of those things that can’t be photographed, at least not easily. It’s amazingly warm and the colors! The white stone railing of the promenade, the sky and the water is blue, and there are golden birch trees in the bright sunshine.

Now a very strong wind is blowing on board, but it’s warm so you can even sit out in a shirt. Returning to the subject of discrimination, this Nemtsev said how good it is to live in Samara because there are no nationalities. And anyway, there are only small, enclosed ethnic groups living along the Volga, and, luckily, they are not causing too much trouble, either. Of course, if they tried to do so, then what was left of them would also be wiped out. The English guy added that he cannot understand the Austrians – why they let their empire disintegrate. (I mean the monarchy). For them, colonization and annexation are forms of glory; it’s lucky that I didn’t understand what they were saying at the time, because otherwise I should have given them stick, which, of course I wouldn’t have done. But still, to drink with this lot?

Ilyinka is a wonderful place, and judging by the port, Chuvashians live here. There are wooden houses built on verdant hills among golden birch trees, there is forest almost everywhere, the houses are under the trees.

Kosmodemiansk is already the land of the Mari. I managed to talk a little with two old Mari women, I also told one of them how beautiful this street was and how lovely the wooden houses were. To this she says: This? Well, that’s shabby, the nice ones are the new eight- and ten-story buildings. Fortunately, you cannot see them from here. People in Samara were also very proud of their concrete monstrosity: their “beautiful” new library building. An old woman there asked me why I was taking photographs, I told her how much I liked the old wooden houses – what do you like about this crappy old house, there are beautiful big modern buildings over there.

Igor’s latest comment – it is a pity that Stalin did not have time to resettle us, Hungarians on the Volga, because that’s where we belong. But he thinks of himself as belonging in New York, he longs for it, he just doesn’t realize that he doesn’t feel good even at home with such a load of prejudices, let alone in America or anywhere else. In the evening I had business talks with the sailor cadets, and continued the conversation with one of them even afterwards.

October 4.

Today we moved over to Mikhail Nazarov, as our previous ship only came as far as Nizhny Novgorod – which was temporarily called Gorky. This ship is smaller than the Sergey Lazo and not so elegant, either, but the bed is finally more comfortable. It was built in Óbuda in 1959. We spent the entire day in the city, getting here at seven in the morning and only moving on at six in the evening. Fortunately, the old town was spared both in war and in peace, the buildings are beautiful, the walkway from the port to the city had a Prague-like feel to it. There is a castle and a long promenade with a fantastic view of the Volga and 1349 stairs to go down to the shore – I didn’t count them, a local old man told it to Igor. We also went into a synagogue, but Igor deliberately chose not to come in – because he is not Jewish. A priest (or rabbi) said that it was only returned to them in February, so it was furnished only in a slapdash fashion. We went to the local Museum of Fine Arts, where there were also paintings by a lot of painters known from Russian classes, like Repin, Levitan, Serov, Surikov, and one Shishkin, which is also in my album. From here too, our ship sailed off accompanied by military music. Our newest travel companions are teenagers, who are making an extraordinary amount of traffic between the cabins, the doors are constantly slamming.

October 5.

In the morning, the radio announced which places we were passing by, what was there to see. At night we passed the Gorky Reservoir, where, as the radio proudly reported 330 settlements were destroyed for the sake of widening the Volga river bed. There was a little sunshine in the morning, we passed by beautiful villages, the wooden houses are painted in all sorts of colors, even lemon-yellow. Then the sun went down and it got very cold. There is no lunch today, but a “second breakfast” because we arrive in Kostroma at lunchtime. At first all I could see was a crowd of concrete buildings, I was already scared where we had come, but, fortunately, we quickly left those behind. We crossed to the other side of the river in a small boat, but then I saw that it was not the Volga, but the mouth of another river (the Kostroma). Here they showed us a monastery, and there were two other churches, one made entirely of wood, but these were not open. Kids were running to us on the street, they immediately thought I was American, I think because of the ostentatious Kodak label on my bag. I said I was only Hungarian, they got less excited, but asked if I had any dollars and they wanted to sell me all sorts of souvenirs. When we got back to the boat we still had some time to climb up a mountain and see this part of the city as well, of course only sort of in passing. Crows were croaking everywhere, and here too there was a church, surrounded by a fairground. A rectangular space is enclosed by white buildings, and shops are both outside and inside. The surrounding houses are also beautiful, but the most ostentatious erection is the statue of Lenin, which is better visible from the water than any church. Our ship continued its course to the tune of the usual military music.

October 6.

This ship is way more annoying compared to the other. There is no quiet corner to hide. There are two common rooms in total, but only one of them has a view. This is the lounge and TV room, which is in the bows and you could best see the landscape from here. But you can’t because these kids behave like preschoolers here. The TV and radio are on full blast, and the kids simultaneously hammer the piano, chase each other and scream. Of course, there is usually no broadcast on TV, just white noise. But if there is, they draw the curtain and are sitting in the dark. There is a video room below without any view, and they even smoke inside. The cabin also stinks, especially since the window doesn’t open; so only the top hallway remains where there are four armchairs, but everyone is running around and you can only see one side, so you have to keep commuting between the two windows while the radio is roaring everywhere.

In the morning we went through another lock. Five ships were squeezed into the chamber. As we ascended to the height of the shore, a cat and a horse came to the railing, the latter was fed by the passengers. After Uglich, there is again a widened reach where populated areas had been flooded and church spires are said to protrude from the water. After a long wait, I finally saw one, but no more showed up, though I was running from one window to the other so I wouldn’t miss out. They say that at lower water levels more of them can be seen. It was three degrees in the morning, and it didn’t get any warmer, so it wasn’t possible to stay on board for long. But anyway, the radio is roaring there too, there is a constant rough-and-tumble going on, which would not be a problem in itself, but people don’t even look at the Volga. And to top it all, they have gold teeth, even the girls, though they are only 16 or17 years old. In addition, there is cleaning up all the time, if I accidentally sit down in a quiet corner, someone immediately comes with a vacuum cleaner or a broom, driving me away, or they are mopping the floor and you either cannot go that way, or the floor is slippery. Right now, I almost fell down the stairs, but I managed to grab a crossbar at the top. There’s Tartar beer in the buffet, I’m sipping it.

1993

June 5.

It is a quarter to 2 at night, and it is still not completely dark. We traveled all the way down the Neva, and now we are voyaging on Lake Ladoga aboard the Petrokrepost. I saw a UFO around 1 a.m. It appeared twice in the western sky against the full moon. At first I noticed a bright spot that was larger than a star but higher than the lights on the coast. Unfortunately, it soon disappeared, but I kept watching that place and it reappeared approx. ten minutes later, now I saw it a little bigger, it flickered and flared as fire flickers and flares; a supernova must be like this when it appears on the sky, only it disappeared pretty soon again, it lasted for around half a minute.

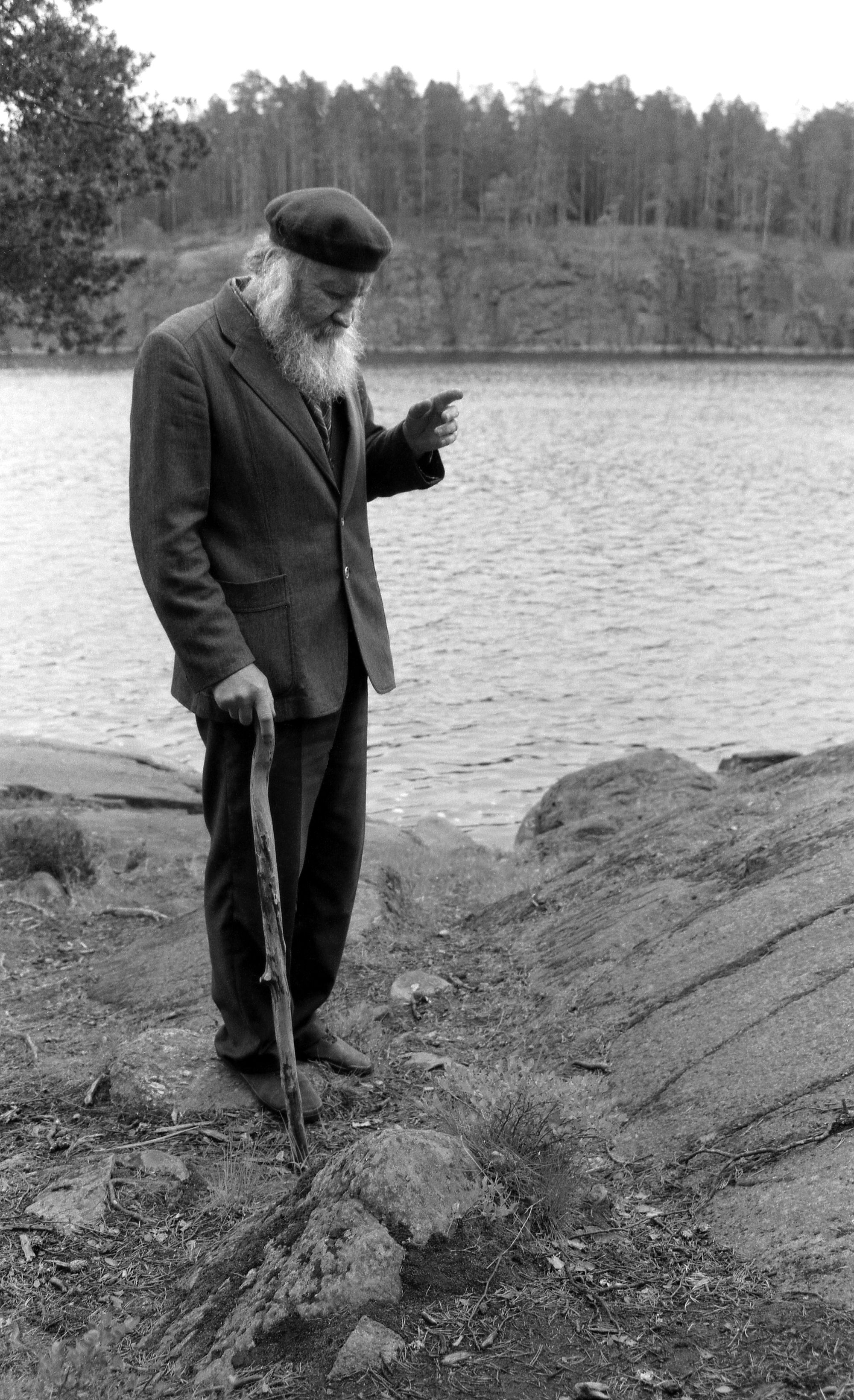

In the morning we arrived at the island of Valaam in the northern part of the lake. There are newly repossessed churches and monasteries here, in the morning we went on a trip on foot, in the afternoon we took a small boat to the other part of the island to see the largest church. I liked the morning tour better, we went through forests, there were also small lakes and you could see the big water from the mountain. There are fantastic landscapes in America too, but here it appeals to your heart too. I was almost happy throughout the entire trip, I fell in love with this landscape and the Russian people. Full-bodied dames, long-bearded orthodox priests, snub-nosed children. My favorite was the guide, a grey-haired old man, with his big strides he always took the lead at the head of his group, reciting poems leaning on his stick, not just babbling the official text. After all, it was also just a group of tourists, but I felt that these people respected the nature they came to visit. In America, I somehow saw the crowd as a bunch of bloodsuckers, at Big Faithful I thought I was also part of this robbery going on against the holy places. There, somehow, the whole landscape with its strangeness is reduced to a mere attraction that can be bought for money.

There were some crazy people bathing in Lake Ladoga, even though both the water and the air was terribly cold. I dreamed of a green kitten on the boat, it was like underwater moss, almost black, but dark green in the light.

*

We went out to the train station in the evening, but in this country things don’t go the way that you just buy a ticket at the ticket-office, because the touts are buying up all the tickets early in the morning, so you can only bargain with them. Eventually we managed to travel from Piter to Tver, and from there by bus to Torzhok. Petya came with us, Igor went completely crazy, he was drinking non-stop, walking with six million rubles in his pockets and telling everyone about it. In Torzhok, among other things, we visited a monastery, which had been a prison until now, and climbed the church tower. The janitor told us that he had lived here for twenty years, which means he was either a prisoner or a prison guard. The monastery has now been returned to the church and renovations and excavations are under way. In the courtyard I saw human bones gathered in a crate, and bones also stood out from the wall of a large pit. I tried to dig out a skull, but the archeological nachalnik [boss] asked me what I was doing so I could only photograph the calf bones, in any case it was very likely that these were the bones of the prisoners who had died here.

Originally, a hundred dollars were set aside for Torzhok as I planned to take the train from Piter to Simferopol, but, to be able to see Torzhok, we eventually were flying from Moscow together. Until then we were traveling by train but, of course, at the airport there were the usual Soviet complications: there were no tickets for the plane until the last minute, and then suddenly there were, but by then there was no time for me to calculate the exchange rates, so the tickets were issued in rubles with an additional cost of three dollars. There is a chaotic hustle-and-bustle all over the airport. Adults are nervous, struggling with huge amounts of luggage, children are crying, anxiously clutching their dogs, cats, parrots, who also make their voices heard. Our tickets were reserved with the Ukrainian airline, but a fight broke out there, and no one could be talked to. And the Russians know nothing about it because their computers are not connected with the Ukrainians. Petya is threatening them with an international scandal. They promise to take action. In the end, the plane is waiting only for us, full of empty seats, of course.

From Simferopol we took a taxi to Koktyebel for 15 dollars. Of course, this can only be done by those who have the money, otherwise there is no transport.

Our accommodation is in the Blue Bay pansionat [resort], which most closely resembles a pioneer camp, but there are no pioneers here, only entire families with countless numbers of children of all ages.

A statue of Lenin was erected in Odessa, but it was badly made, so one day the head fell off. The sculptors were ordered to make him a new head, but they did not look at the original statue, so it was only at the unveiling that Lenin turned out to have two caps: one on his head, one in his hand.

Ukrainian money is called karbovanets, or coupons for short, and it looks like money from the board game Gazdálkodj okosan [the Hungarian, socialist version of Monopoly]. I kept one as a keepsake, it got wet and the dye ran on it. They do not officially exchange rubles at the bank because they are now independent and prefer dollars. They also charge foreigners an entrance fee of fifty dollars, but there is no service on the beach or anywhere else that would attract a single western tourist, and in their great pride they even call foreigners morons. That’s how they want to live off them.

Yesterday we went on a trip to Sudak by a small boat. The hotel did not exchange money, we had to walk and walk for half an hour along the beach to get something to eat and drink. The trip itself was a miracle of organization, in that there was neither breakfast nor lunch, some alcoholic drinks had been ordered, all of which the museum director drank with his small circle of friends the night before, luckily we were back in time for dinner. The conference itself is being held in a similar spirit, no accommodation is paid for, and everyone is getting here as best they can. Still, there are some determined American ladies, and German, Italian, French researchers, and the three Hungarians, and me, the free rider. The evening life here is very noisy, I sit in the crossfire of two discos at the foot of the Dekabrist statue.

Igor from Novosibirsk has arrived with his family. On the six-hour flight, passengers were given a glass of water as no food was found in Novosibirsk. They then landed in Sochi to refuel, but the Russians did not want to give them any because the plane did not belong to Aeroflot but to a foreign (Ukrainian) airline. In the end, they did sell them fuel for dollars, but it took another six hours.

*

On June 20, we moved to Gelendzhik. There were also passengers standing on the bus, and as many times as there were checkpoints on the road, they were asked to disappear, then the entire middle row squatted down between the seats. At the Ukrainian border check-point, they asked if there were any foreigners besides us, an old Russian woman remarked that everyone was a foreigner who was Russian.

*

Forty swans lived in this bay, but by spring there were only twelve left, the rest having been eaten by the people.

*

Igor’s ancestors were Germans living by the Volga, and during World War II his parents and the entire colony were deported to Siberia so that they wouldn’t collaborate with the Germans. Then, after the war, they were declared war criminals because they were Germans. The parents lived in a henhouse for more than ten years, Igor was also born there. In cold temperatures of -50 degrees, they scraped the ice off his face in the morning. They were only able to move into an apartment in ’56, when he was two years old. But he hasn’t been sick since, never in his entire life!

This Igor took the entrance examination to the Music Academy eight times. He always scored the highest scores, received a letter notifying him that, congratulations, he had been admitted, then a few days later came the usual phone call saying that they couldn’t admit him after all because they found out that he was singing in a church choir.

The children in the orphanage come out to the beach every day, forming a line in their uniform bathing trunks by the water, four or five at a time can go for a swim for a few minutes, then they come out and the next four can go in.

In Gelendzhik, a Greek man said he saw on TV that in Afon there were dead people lying on the streets and no one was burying them. The idea of sending a telegram to Sukhumi proved to be too optimistic. I hope they don’t respond because they have fled. People say the war will last a long time.

***